what should the nurse discuss with new parents to help them prepare for infant care?

- Research article

- Open up Access

- Published:

Parents and nurses balancing parent-infant closeness and separation: a qualitative study of NICU nurses' perceptions

BMC Pediatrics volume 16, Commodity number:134 (2016) Cite this article

Abstruse

Background

When a newborn requires neonatal intensive intendance unit (NICU) hospitalization, parent and infant experience an unusual often prolonged separation. This disquisitional intendance surroundings poses challenges to parent-infant closeness. Parents desire physical contact and holding and touching are specially important. Evidence shows that visitation, holding, talking, and skin to skin contact are associated with amend outcomes for infants and parents during hospitalization and beyond. Thus, it would be important to sympathise closeness in this context. The purpose of this study was to explore from nurses' perspective, what do parents and nurses practice to promote parent-infant closeness or provoke separation.

Methods

Qualitative methods were utilized to reach an agreement of closeness and separation. Following ethics approval, purposive sampling was used to recruit nurses with varying feel working different shifts in NICUs in two countries. Nurses were loaned a smartphone over ane piece of work shift to tape their thoughts and perceptions of events that occurred or experiences they had that they considered to be closeness or separation between parents and their hospitalized infant. Sample size was determined by saturation (xviii Canada, 19 Finland). Audio recordings were subjected to inductive thematic assay. Team meetings were held to talk over emerging codes, refine categories, and ostend these reflected data from both sites. Ane overarching theme was elaborated.

Results

Balancing closeness and separation was the major theme. Both parents and nurses engaged in actions to optimize closeness. They sought closeness by acting autonomously in infant caregiving, assuming decision-making for their babe, seeking information or skills, and establishing a connection in the face up of separation. Parents counterbalanced their want for closeness with other competing demands, such equally their own needs. Nurses balanced babe care needs and ability to handle stimulation with the need for closeness with parents. Nurses undertook varied actions to facilitate closeness. Parent, infant and NICU-related factors influenced closeness. Consequences, both positive and negative, arose for parents, infants, and nurses.

Decision

Findings bespeak to actions that nurses undertake to promote closeness and assistance parents cope with separation including: promoting parent decision-making, organizing care to facilitate closeness, and supporting parent caregiving.

Groundwork

Immediately after nativity the natural environment for a newborn is to be shut to their caregiver [1, ii]. Physical closeness is defined equally parent and baby existence spatially shut, while emotional closeness refers to feelings of an emotional connection to the babe such as feelings of love, warmth and amore [3]. Evidence suggests that afterward birth, physical closeness between parent and newborn may contribute to the development of attachment, and both parent and infant play a office in this process [4]. Parent behavior can contribute to differences in infant development, and parent exposure to infant cues and somatosensory stimulation can enhance parenting behavior and care [5].

Current understanding of the neurobiology of caregiving indicates that parents' neurological system becomes interconnected with the newborn'southward immature nervous system resulting in symbiotic regulation [vi]. In this feedback system, the parent supports the biological and behavioral needs of the newborn, conversely newborn behaviors precipitate physiological processes that establish the parent-baby relationship and also stimulate neurological systems that support parental well-beingness. Contempo evidence shows that both the brain and body of mothers undergo changes to back up the development and maintenance of caregiving behaviors [7]. Imaging studies of mothers and fathers reveal that specific regions of the brain, hypothesized to be involved in parenting beliefs, are activated in response to exposure to infant-related auditory or visual stimuli such as cries [7–ten]. Moreover, structural changes accept been observed in specific regions of the brain amongst mothers [11] and fathers [viii] in the early postpartum. These changes may crave exposure to the infant [11], and the effects of prolonged separation at this time on these neurobiological processes in parents are non known.

When a newborn requires hospitalization in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), parent and baby experience an unusual separation that may final weeks or months. This critical care environment poses many challenges to parent-infant closeness. NICU parents want concrete contact [12, 13], and holding and touching are particularly of import and rewarding [14–17]. Mounting evidence, outlined below, shows that various forms of contact, such as visitation, belongings, parent talk, and skin to skin contact, are associated with better outcomes for infants and parents during hospitalization and beyond. Greater visitation and infant holding is associated with better babe neurobehavioral development at discharge [18]. School-age NICU graduates whose mothers visited daily had fewer behavioral and emotional problems compared to their peers who had fewer visits [xix].

NICU infants receiving added exposure to recordings of their mothers' voice bear witness lower heart rate [20], improve feeding outcomes [21, 22], greater auditory cortex growth [23], better visual attending and neurofunction [24], higher Griffiths Development Quotient scores and before use of two discussion sentences [25]. Infants of mothers who spoke and sang to them daily had college oxygen saturation levels and fewer negative critical events [26]. Furthermore, exposure to greater parent talk during hospitalization is associated with greater infant vocalizations at discharge [27], and better language and cognitive development in toddlerhood [28].

Peel-to-pare care, in which an infant lies on a parent's bare breast, is an important class of physical closeness now promoted in NICU intendance, and is associated with benefits for infants, parents and their relationship. Pare-to-skin contact accelerates the development of baby's sleep construction [29] and brain maturation [thirty], and lowers stress reactivity [31]. It is associated with decreased bloodshed, lower risk of sepsis and readmission to hospital [32]. Other benefits include shorter NICU stay, longer duration of breastfeeding, decreased parental cortisol, improved parent well-being and decreased anxiety, optimal parent-infant interaction, improved maternal attachment beliefs and greater parental competence after discharge [33–41].

Policies apropos visitation and overnight stays, every bit well as actual visitation time and skin to skin intendance vary widely across units and countries [18, 42–44]. Unit of measurement policies, and the behavior and attitudes of NICU nurses play a function in parent presence and interest. Nurses can human action every bit gate-keepers controlling parents' admission to their infant [sixteen, 45]. Some experience the need to seek permission from nurses to handle their infant, and their relationship with nurses influences their ability to enact their parental role [15, 46, 47]. Nurses may discourage parents from treatment their infant when they consider this detrimental to infant well-beingness [46], and believe that skin to skin contact limits their access to infants [48]. When parents are confident and actively participate in daily infant intendance, nurses can experience less involved and less knowledgeable, and thus superfluous [49]. In contrast, nurses besides foster parent involvement past pedagogy them how to care for the infant, coaching and demonstrating care, encouraging and supporting parents, enabling parent presence and providing information [50–52]. Parents perceive that nurses' caring attitude and open communication are necessary preconditions for parent-infant interaction and bonding [47, 53]. Moreover, greater parent involvement in intendance and decision-making is seen by nurses as beneficial for them besides, leading to more than meaningful work and improved work satisfaction [54].

Given the growing bear witness that supports the importance of various forms of parent-infant proximity for parents, parenting and infant well-being, and the challenges of supporting closeness in the NICU; it would exist important to farther our agreement of closeness in this context. To our noesis, no previous studies have described the nature of closeness and separation events between parents and infants during an NICU hospitalization, and what gives rise to such events in this surroundings. What nurses do to promote closeness or provoke separation has not been explicitly explored, and it would be important to understand their perspective to promote parent-infant closeness in practice. Thus, the questions guiding this inquiry were: What do NICU nurses consider to exist closeness or separation events in the NICU? What do nurses perceive that parents practice to be close to their infant? What do nurses retrieve they practice to promote closeness or cause separation? Qualitative methods were utilized to attain an understanding of closeness from the perspective of nurses in two countries.

In add-on, to minimize recollect bias a new innovative smartphone awarding was employed to collect rich data. The mobile phone awarding programme HAPPY "Handy Awarding to Promote Preterm babe happY-life" was developed every bit a tool to collect information from staff and parents of newborns by one of the report investigators. The application allows study participants to easily record their thoughts soon later on they have feel a critical incident, in this case closeness or separation between parent and infant.

Methods

Settings and participants

Data were collected from nurses working in two level Three NICUs with different architecture in two countries. The first site was a unit in Turku Republic of finland with eighteen beds and 600 admissions per year including fifty to seventy infants weighing less than 1500 g at nascence. The unit of measurement has ten single family rooms with sleeping accommodations for both parents at their infant's bedside, and three pods of two to iv beds. The second site was a 34-bed open up ward unit of 400 square-meters in Montreal Canada with 650 admissions per year, including approximately 115 infants built-in less than 1500 g. Parents are able to be nowadays during medical rounds and cellular telephone use past staff and parents are permitted in both units. At both units, both parents are able to stay overnight: in Turku in the unmarried family rooms on cots at their infant'due south bedside and in Montreal in a parent room adjacent to the open ward unit (not at their babe's bedside) where only 1 parent could stay overnight.

The study protocol was canonical past the research ideals commission at each site prior to data collection. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant, and they were bodacious that participation was voluntary. Particular attention was paid to assuring the privacy of potential families or other staff described in the nurses' recordings. Study participants were asked not to proper name individuals in their recordings. If inadvertently whatsoever identifying data was included in a recording, this information was not included in the transcript.

Nurses were informed nearly the study at unit meetings, via an email detect sent past the unit of measurement manager, and by posting information brochures about the report on staff detect boards. Nurses interested in participating contacted the research team past telephone or e-mail for further information, and if they agreed to participate, a time to meet was arranged to obtain written informed consent. Research staff also visited the unit and approached staff asking if they had heard near the study and would be interested in participating.

At each site purposive sampling was used to include nurses with varying levels of work experience and different periods of ascertainment (i.east., twenty-four hour period, evening, or night). At get-go, any nurse coming together the inclusion criteria and agreeing to participate was included. Every bit recruitment proceeded, the inquiry squad examined the work experience and shifts worked of the participants to date, so sought to enrol subsequent participants who would broaden the range of experience and shifts during which recordings were made. Sample size was determined by data saturation, thus information collection continued until no new categories were evident. This occurred later there were xviii participants at the Canadian site and nineteen at the Finnish site.

The characteristics of participants and their work circumstances on their written report 24-hour interval are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. All the participants were women. There were a few eligible men at the Canadian site just none agreed to take function. Nurses in Canada were 28.4 (SD = 4.7) years of age on average, and those in Finland 38.7 (SD = 11.four) years. Although the majority worked in the NICU for more than a yr, 7 of 37 (18.9 %) had less than a year of feel. Nurses recorded their thoughts primarily during a day shift, however 9/37 (24.3) recorded on evenings and 4 of 37 (10.8 %) on dark shifts. Although a few nurses participated while working a night shift, there made no entries made between midnight and 7:00 am primarily considering parents were not nowadays or asleep. One-half of the recordings were fabricated of infants requiring acute or intermediate care, and half step-down care.

Design and data collection procedure

An interpretive descriptive study was conducted [55]. Nurses were asked to employ the HAPPY application over the course of ane work shift. Android mobile phones with the application installed were made available to them prior to, or at the beginning of, the shift chosen for information collection. Nurses completed a groundwork information form, and a member of the research squad provided verbal and written instructions on how to use the HAPPY application. They were instructed to use the application when they experienced an outcome they considered to be closeness or separation to tape their description of what they experienced. For example, if a nurse removed a baby from skin-to-skin contact with a parent for blood sampling, afterward this event the nurse would open up the application on the phone and classify the event every bit closeness or separation by clicking the advisable button labeled 'separation' or 'closeness'. After classifying the event, they would describe aloud where the events occurred, what happened, and why. If at the fourth dimension of the event, the nurse was unable to record their detailed thoughts considering they did not have time at that moment they could quickly open the application and insert a bookmark. When it was convenient, they could return to the bookmark to record their thoughts.

At the finish of the shift or the next day, the telephone was returned to the inquiry team. A team fellow member downloaded the audio recorded data onto a study computer, and the recording was deleted earlier the phone was given to a subsequent participant. Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim past research staff fluent in the language of the recording (i.e., English, Finnish or French). Transcripts were labelled with an id number, any identifying information removed, and and then captured into Nvivo software for analysis [56].

Data assay

To describe the events recorded by participants, we used descriptive statistics to study the full number of recorded entries, average number per participant, and the pct classified by participants as closeness or separation events. Analysis of the information was iterative and began with the first transcripts collected, and continued throughout the data collection period. Inductive thematic analysis [57], a widely used analysis strategy in the health sciences to answer questions of clinical involvement, was used. Transcript entries were coded at the site where the data were collected by an investigator fluent in the linguistic communication in question. Showtime, each transcript entry was read carefully several times by an investigator, and open-coding used to assign codes to meaningful sections of data describing closeness or separation using Nvivo [55]. To ensure trustworthiness, at regular intervals during information collection and analysis meetings of investigators were held to discuss emerging codes and conceptualizations, refine categories, reach consensus on these and confirm that these reflected information from both sites. As data collection continued, codes were compared and contrasted and somewhen organized into categories, and the relationship between these categories examined. Finally one overarching theme, a thread encompassing all categories, was elaborated and a dimensional matrix employed in this procedure [58].

Sample excerpts from the nurses' entries are provided in the results section to illustrate the categories. These are labeled with the participant's identification number and site ("C" for Canada and "F" for Finland). These samples volition let readers to assess the transferability of the findings to their own setting. For the purposes of this report, examples of nurse entries made in a language other than English were translated past an investigator fluent in that language.

Results

Study participants fabricated 220 entries with the HAPPY application, and 158 (71.eight %) were classified past them as closeness events and the remaining 62 entries (28.2 %) every bit separation events. Thus, they described more closeness than separation events. Of the 78 entries made on day shifts, 78.four (Canada) and 63.8 % (Finland) were closeness events and on evening shifts 71.4 (Canada) and 70.4 % (Republic of finland). At both sites, the average number of entries per nurse was five, with a range of zip to 18.

Closeness and separation events

A range of events were described by nurse equally closeness events (Table 3). Nurses utilized three criteria to decide if an event was closeness or separation. The duration of visitation or presence played a role in nurses' perceptions. If parents appeared briefly at the infant'due south bedside and departed before long afterwards, nurses considered this to be separation. Conversely, spending a corking deal of time at the bedside was considered an indication of closeness.

The quality of parent's presence was also used to decide whether an event was separation or closeness. When a parent was physically present only non continued or involved with the infant, nurses considered such events to be separation. For example, one nurse described this separation event: "The female parent and father are upset nearly naming the babe. … Instead of being close with their infant, they're exterior of the unit now for one-half an hour arguing on what they're going to name the baby. … (N13-C).

Lastly, the comfort level of both parent and babe during events was some other element taken into account. During a feeding for example if parent and infant were comfortable, and the infant was feeding well, this was considered closeness. If the feeding was difficult for parent or babe, so this viewed as a separation event.

In many instances where nurses described separation events, they noted parent behaviors that suggested that the parent was experiencing difficulty with the separation. Hesitation, signs of emotional distress, and repeated looking back at the infant were behaviors unremarkably noted.

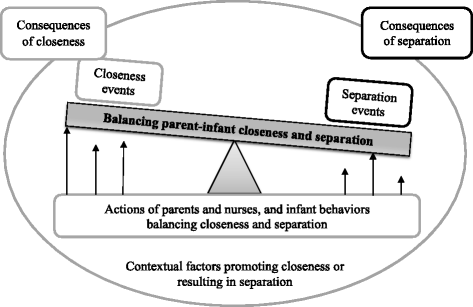

Balancing closeness and separation

Balancing parent-babe closeness and separation was the major theme or thread encompassing all the categories (Fig. one). Closeness and separation events took place between parents and infants and parents and nurses could exert some control over these events. Both parents and nurses engaged in actions or efforts to optimize or tip the balance towards closeness despite the overall context of separation. Parents needed to rest their desire for closeness with their hospitalized infant with other competing demands on their time, including the needs of their spouse and other children, as well equally their own personal needs for nourishment and residual. When parents confronted a separation event, they frequently engaged in deportment to minimize separation and promote closeness. One nurse described this instance of a parent undertaking such activity:

The overarching theme "balancing parent-infant closeness and separation" and the related concepts

This morning … at that place was a father who came in whose baby is going to be transferred to another infirmary. He was not able to stay for very long, nevertheless he put a little music box next to his babe to provide comfort to his baby. I believe this was an intervention that the begetter did that allowed him to feel close to his infant despite simply beingness able to be there for nearly 10 minutes as he has a busy 24-hour interval ahead of him (N01-C).

Nurses also engaged in varied deportment to facilitate parent-baby closeness and minimize separation. They sought to residuum the need for parent-baby closeness with the infant'due south intendance needs and ability to handle stimulation. Infants likewise played a part in this balancing procedure, admitting a lesser 1, through their behaviors and responses. A number of parent, infant and NICU-related factors influenced parents' and nurses' efforts to rest closeness and separation. Lastly, there were consequences, both positive and negative, that arose from closeness and separation events for parents, infants, likewise as nurses.

Actions of parents and nurses, and infant behaviors that remainder closeness and separation

Every bit noted before, both parents and nurses actively engaged in behaviors that balanced closeness and separation. A myriad of parent actions were considered by nurses to promote closeness. Parents sought to balance closeness past seeking physical proximity to their infant. They did then by being nowadays at the bedside and engaging in whatever form of concrete contact was possible with their hospitalized infant at the time.

The most frequently described parental activeness was agile interest in infant care. When parents cared for their infant independently nurses viewed this every bit tipping the rest in favor of closeness. Acting autonomously in infant caregiving and being comfortable doing and so is exemplified by this instance: "The male parent of a set of triplets arrived into the pace-down unit just now. … He was non accompanied past his wife… He immediately went and started doing the intendance for one of his sons. I could see that he seemed very comfortable and he seemed to have a look of … pride in his eyes that he was able to give the canteen to his baby" (N01-C).

Assuming decision-making about babe care or treatment was another parental action that nurses considered promoted closeness. In a like vein, parents efforts to direct their infant's care by requesting that staff perform certain caregiving activities or perform these in a particular way, or limiting staff interest in caregiving was a related category of deportment. In i case a mother called the unit and requested that the nurse not perform whatsoever infant care that morning so that she could do so when she arrived.

Parents seeking information near their infant'southward medical status or care was considered to assistance accomplish closeness. Ane nurse remarked: "To me … the parents calling to enquire 'How is my babe doing, what is the weight this morn, did she swallow well'… information technology is a sign of interest in the baby and a way to be close" (N04-C). Verbal statements or other actions undertaken that reflected parent's interest in the babe or desire to be involved in care was some other related form of activity noted. In one situation a mother asked the nurse if she could provide care for her baby that she had not previously performed. Similarly seeking feedback, communication about or acquiring skills in infant care were also viewed to promote closeness.

When separation was required, parents engaged in familiar goodbye rituals such as bidding goodbye, kissing, and promising to come back equally presently as possible to cope with these events. Parents also undertook actions to establish a connection during a separation. They did and then past leaving objects such as a music box or toy with their infant, calling the unit and asking the nurse to tell the baby that his parent loves him, or taking pictures of the babe to take home.

In this circuitous intendance environment, strategies that nurses employed to residue closeness and separation were also varied. Supporting parents' autonomy in infant care was a central strategy. Nurses promoted parent autonomy by teaching, demonstrating care or procedures, engaging with parents to jointly provide care or by expressing their availability to be of assistance if needed as the parent performed caregiving. Only the Finnish nurses described helping parents learn near infant beliefs. They shared their observations of infant behaviors or preferences with parents, or engaged parents in making observations of infant behaviors.

Promoting and respecting parent'southward function as the decision-maker for their infant was a way to rest closeness and separation. For example, i nurse had a give-and-take with parents about when to practise a care procedure. In a similar vein, providing and or facilitating admission to information almost the infant'due south status or care was considered to promote closeness. Nurses also advocated on parents' behalf with other staff: "The baby was very hungry. I discussed with the mother about her baby's fasting and promised to ask the doctor if the baby can take some breast milk although the operation was done just two days ago". (N16-F)

Nurses encouraged parents to be present and take physical contact with their infant (e.g., encouraging touch or visual contact when that was all that was possible, or breastfeeding and pare to skin contact). Controlling aspects of the NICU environment, such as providing privacy, reducing noise during parent-infant contact; and structuring intendance to support parent involvement (e.g., setting equipment upwardly to facilitate skin to skin contact) was another category of nursing deportment. "The baby is intubated. The male parent lifts the baby very calmly back into the incubator from peel to peel contact on his female parent. He has evaluated that the boy is fix for the transition. The baby is awake, non asleep. The transition goes well. My role every bit a nurse is to move the ventilator and the tubes while the begetter places the boy nicely back into the incubator." (N13-F)

Providing emotional support was viewed as enhancing closeness. For instance, nurses provided positive feedback to parents about their abilities to intendance for their infant or reassured them nearly their infant'south well-existence. Lastly, nurses recognized parents' struggles with separation events and tried to ease these events past promising to take good intendance of the babe while the parent was absent.

Although most of the nurses' entries involved promoting closeness, there were situations in which their actions resulted in separation. NICU nurses sometimes decided that stimulation to the infant needed to be controlled and this provoked a separation event. Once, the infant was sleeping and the nurse recommended that the parents not wake the baby to hold him every bit they wished to do. When nurses intervened to provide a required handling, such as oxygen, this as well resulted in separation. If parents requested information and the nurse was unable to provide it, this was perceived to contribute to separation. Occasions too arose where a parent sought the nurse's assistance while caring for their infant; however the nurse was occupied and unable to reply to the asking, resulting in separation.

The behavior of the infants played a role in balancing parent-infant closeness. Infant signals such every bit crying, fussing, facial expressions, vocalizations, and change in vital signs typically prompted a parental response. In this example the babe emitted a bespeak and the parent responded, resulting in a closeness result. "The infant was in the crib while the mother was pumping her milk and the begetter was helping, a moment of closeness occurred when each time the baby stirred or made a audio, the father would get upwards from his chair and check on the infant and comfort him by patting him, offering him the pacifier and speaking to him softly to console him" (N17-C). In contrast, babe crying while parents engaged in caregiving could provoke feelings of inadequacy, and this was viewed as a separation event.

Factors influencing closeness and /or separation

Embedded in nurses' descriptions of closeness and separation events were parent, nurse, infants, and contextual factors that nurses perceived influenced the balance between closeness and separation. Parent characteristics such as lack of child intendance feel, distressed emotional state, and poor health status (eastward.one thousand., pain, fatigue or hospitalization) tipped the balance towards separation. Worry about the babe's medical condition or fear of the infant's or mother's death were examples of these. One Finnish nurse explained: "I encouraged the father to agree the baby as she was crying in the cot, but at that betoken he was not able to do so because of all his worries (the female parent was in the ICU). He needed back up from me more than closeness with the baby" (N12-F). In contrast, when a parent was confident in their ability to care for their infant or had previous child care feel, these attributes promoted closeness. Nurses own beliefs played a role. When they believed that parents should be the main caregivers this enabled closeness.

The infant's physiological stability could bear on closeness and separation. When an infant experienced an agin event such every bit desaturation or bradycardia while in the parent's intendance, nurses noted the parent verbally expressed or appeared to feel inadequate. Conversely when one female parent who was afraid to hold her infant noted that the infant's vital signs remained stable when she held him, she relaxed and enjoyed the physical closeness.

With respect to contextual factors, the overall atmosphere of the NICU, also equally specific aspects of it, played a role. When the environs was quiet and calm, this enabled parent-baby closeness. As one nurse stated: "In a single family room the begetter is holding his boy in skin-to-skin care and the mother is sitting at the foot of the bed. The atmosphere is at-home and convivial which contributes to closeness" (N13-F). While the surround could promote closeness, it could also influence separation. Lack of privacy, equipment noise and the overall technological temper were viewed equally contributing to separation. Infant intendance requirements such as treatments or procedures, the incubator, equipment or devices were other environmental factors as illustrated in this instance: "The infant had an urinary catheter and was intubated so the parents could non go close to him" (N14-F).

But Finnish nurses considered that how care was organized in their hospital influenced closeness. They reported that because mothers and infants were hospitalized in separate units women were forced to leave their infant and the NICU to go to the maternity ward for their own medical care: "The female parent had to put the infant into the cot and go back to her own ward for breakfast and morn wash" (N06-F).

When parents attended to their own personal needs for residue and nourishment this contributed to separation, every bit did attention to the needs of other family members. Parents had to balance other responsibilities that required their time and attention, such as other children, family members and employment. Some fathers needed to attend to the needs of their partner particularly when the female parent herself was unwell after childbirth. Parents of multiples confronted particular challenges as they sought to residual closeness with more than i infant.

Consequences of closeness and separation

Nurses identified consequences of closeness and separation events for parents, infants and nurses. Nurses balanced these consequences when making decisions about infant care. The main dilemma for them was whose needs should be given priority; the infants' or parents'? A Finnish nurse expounded on this claiming:

"This pare to pare contact result made me think about whose needs should make up one's mind the timing of pare to peel contact. The infant was in deep sleep in the incubator, and this is of import for development. The parent wanted to accept her in pare to peel contact at that time. What is all-time, that the parent have her babe her close or that the baby should remain in deep slumber?" (N04-F).

Closeness events typically gave rise to positive consequences for parent and or baby, nonetheless this was not e'er the case. Positive consequences for parents included improved parental mood (e.one thousand., happy, proud), greater comfort in caring for their infant, improved appointment with the infant, ameliorate maternal milk production, and feeling useful. One nurse reported: "I gave a bath demonstration for baby Y today and mommy felt really happy to be able to give the bathroom to the baby. She felt comfortable and she felt that she was useful. … Information technology was a practiced thing for her to beginning giving baths to her babe (N07-C). In that location were situations where nurses identified negative consequences of closeness for parents, such as when parents experienced farthermost fatigue when they had extended closeness with the infant and did non get sufficient sleep.

Consequences of closeness for the infant were all positive, and included improved infant state (e.thousand., alert, satisfied, at-home, falls comatose), stabilization of vital signs, and effective feeding. As ane nurse explained:

…mom was standing at the bedside while the nurse was gavaging the baby. Mom had her hand within the incubator and she was trying to at-home her infant downwardly, placing her hands on the baby's head and touching her baby and because of that everything went smoothly and the baby was able to receive her feed a lot more hands and was less agitated and not crying as much considering mom was present (N11-C).

Interestingly, nurses likewise reported consequences for themselves when they were involved in, or experienced a closeness or separation effect. Situations in which closeness events slowed the nurse'south work were evident, withal they made a witting decision to back up closeness despite agin effects on their own work. Nurses also felt touched emotionally when they experienced parent-infant closeness.

In dissimilarity to closeness events, most separation events were associated with negative consequences for parent and/or infant. Negative consequences of separation for parents included feeling out of control or useless and negative mood (e.thousand. anxious, sad, or guilty). One nurse reported: "The baby did a desaturation with the feed of a bottle. This was a separation considering I had to take the baby from the mom. … The mom felt a trivial bit useless at that moment because she couldn't assistance her babe" (N07-C).

When nurses provoked separation, guilt feelings arose. Sadness surfaced when they experienced a separation consequence. Learning could also be a upshot for nurses. They noted that when they volition encounter a similar situation in the time to come, they intend to change their arroyo. In this case the nurse learned what needed to exist avoided to foreclose separation between one father and his infant: "The baby had an I.V. line in the head. The parents came to have intendance of her and when the father saw the I.V. cannula he was terrified. He was forced to leave the room and only able to come back when the baby had a cap on her head. I was and then disappointed for the parents because I did not know nearly the father'south fear and was not able to forestall this separation past putting the cap in the baby's head in advance" (N09-F).

Discussion

The ultimate goal of NICU nurses is to provide a intendance environs that volition support babe development, and concrete and emotional closeness betwixt parent and infant has important benefits for infant evolution. However, there are many aspects of this critical care environment that pose challenges to closeness. Thus a nursing care culture that supports closeness is imperative. We found that from nurses' perspective, both parents and nurses engage in varied actions to balance parent-infant closeness in this overall context of separation. Our findings indicate to intendance practices that could support closeness, the well-being of parents, and parenting in the NICU; and in turn the evolution of infants. Implications for do are elaborated below and summarized in Table 4.

Nurses identified numerous closeness and separation events, and used the elapsing and quality of engagement of the parent, as well as the condolement of both partners during the event to determine if they considered that upshot to be closeness or separation. They considered that physical closeness could facilitate emotional closeness and vice versa. Withal there could likewise exist a disconnection: parents could be physically close but emotionally detached, or physically afar but emotionally connected.

Interestingly our findings coincide with the key attributes of parent-nurse partnership identified in a concept analysis of family-centered pediatric care; namely parent autonomy and control, shared responsibleness for controlling and caregiving, and negotiation near intendance [59]. This suggests that family unit-centered intendance could facilitate NICU parent-infant closeness. From Canadian and Finnish nurses' perspective, fundamental actions that parents engaged in to promote and residuum closeness were acting autonomously and playing an active office in decision-making. On the other paw, nurses counterbalanced closeness past supporting parents to act autonomously in caregiving. For decades, studies accept consistently documented the stress NICU parents feel due to restriction of their parental role and its adverse effects on the parent-baby relationship [16, 46]. In contrast, when parents care for their newborn as they expected to exercise so if the infant had been born at term this promotes a sense of normality, fosters closeness [16], and promotes parental well-being and competence [fifteen, 46, 51].

We found that information-seeking and learning how to care for their babe were parent actions enhancing closeness. Conversely, by providing parents with information, supporting their access to data from others sources, and teaching and coaching parents in developing care cognition and skills, nurses facilitated closeness. Moreover, when parents played an agile role in decision-making and directed babe care this too promoted closeness. Previous studies highlight the significance of information [60] and the challenges parents encounter negotiating with nurses, challenging practices, and insisting that things be done as they prefer [46]. De Rouck and Leys [61] argue there should be "information exchange" between parents and NICU staff: staff provide technical information while parents provide personal information (i.east., their own preferences and those of their infant) to get in as care decisions that are optimal for infants and their families. This process has also been referred to as shared determination-making [62]. For this to happen, staff must relinquish control, truly exchange information and interact in decision-making with parents.

Close Collaboration with Parents and Family Integrated Care (FICare) are new models of NICU care that may benefit families and staff. The Close Collaboration with Parents program aims to strengthen the implementation of FCC by training the entire nursing staff of a unit of measurement to conduct articulation observations of infants' behavior with parents. This individualized data is used for planning infant care collaboratively during hospitalization and the transition to home [63]. Finnish nurses trained in the Shut Collaboration program regard greater parent interest in infant intendance and controlling as beneficial for both families and themselves [54]. Closer relationships with parents translated into more meaningful piece of work and improved work satisfaction.

The FICare model involves parents acting as primary caregiver, taking part in medical rounds and collaborating with professionals in developing the care plan [64]. Nurses and other staff play a secondary role supporting parents, thereby enhancing both parent autonomy and infant well-being. The effects of this model are now being investigated in a clinical trial [65, 66]. Although these models hold neat promise to minimize the adverse effects of a NICU hospitalization for parents and infants, it is imperative to consider that not all parents will desire this level of interest and some may require more time and support than others to assume such roles [17]. It seems likely that parent involvement should all-time exist tailored to parent's personal preferences [59]. For example in this written report, nurses reported separation events when parents declined their offering of contact with their babe or an opportunity to provide intendance.

From nurses' perspective, providing emotional back up to parents was perceived as fostering closeness. Further, parents' psychological and physical well-being was a factor in their power to be shut to their babe and vice-versa, closeness improved parents' mood and well-being. NICU staff need to provide support and resource that parents may require to improve cope with any emotional distress they may experience then they are able to be physically and emotionally shut with their infant. Recently the National Perinatal Association in the The states adult standards for the psychosocial care of NICU parents [67]. They recommended that all parents have a meeting with a mental health professional assigned to the unit inside 3 days of their infant'southward admission, and that all parents should be screened for emotional distress (i.east., depression and post-traumatic stress) [68]. A referral organisation needs to exist in place to provide intendance to those parents who may crave this.

Nurses have a vital function to play in controlling noise and providing privacy to support closeness. It is known that dissonance and lack of privacy are environmental factors that touch on parents' NICU experience [69, 70]. Our study extends this knowledge past highlighting the role that these ecology features play in parent-infant closeness. Staff need to exist cognizant of these factors and minimize their touch on parents. Moreover, the extent to which the architectural design supports closeness needs to be addressed when planning new units [71]. Attention needs to exist paid to unit of measurement décor as it should be more dwelling-similar than institutional [fifty, 72].

Our findings indicated that seeking physical proximity was a key parental action to residue closeness. Parents want to be physically present to form a relationship with their infant. Although phone calls or other innovative forms of remote communication at present being explored (e.thousand., web-cam viewing of the baby from domicile) may help parents cope with NICU hospitalization, evidence suggests that concrete presence and contact remains preferable for parents [73]. This is not surprising given current knowledge of the biological mechanisms underlying parenting and zipper. If physical contact is so disquisitional, early on in the hospitalization nurses need to assess parent visitation and help parents manage barriers to their presence [43].

Nurses strive to remainder the need for parent-infant closeness with the needs of the infant and their ability to handle stimulation. Based on principles of developmental care, staff may discourage parents from treatment their infant when they consider this might be detrimental [46]. Equally seen in this written report, they may remove infants from their parents cover when an adverse consequence occurs. If this is necessary, nurses should do so in a way that minimizes deflation of parental competence. Also they should contemplate whether the event could be managed without removing the baby. The natural environment for an baby is shut to their caregiver and they could recover from adverse events if nurse can learn to work in this new context and support parents also. Lastly, nurses should practise a thorough assessment of the infant'southward power to manage treatment, and prevent adverse events from occurring.

Separation events were typically characterized equally difficult for parents every bit evidenced by the distress nurses witnessed. A Swedish study described variability in parents responses to deviation based on their comfort with the staff, and the stability of the infant'south medical status [69]. Our data also showed that parents engaged in deportment to maintain a connection in the face of separation. Nurses must be cognizant of the difficulty of departures for parents. Together with parents, they can develop an approach to departures that might ease parent's distress. Goodbye rituals, transitional objects and leaving when the baby is asleep seemed to help parents cope. In addition, staff should appreciate the value of telephone contact to parents when they cannot be physically present. Transitions from close contact, such every bit the end of pare to skin care, tin as well be managed with similar attentiveness to parent's feelings.

Limitations and directions for hereafter inquiry

Ane limitation of our study is that participants are likely to be nurses who are interested in promoting closeness and minimizing separation. Nurses described guilty feelings when reporting that they had caused a separation event, as they may perceive that closeness is more desirable than separation. This may explicate why at that place were fewer separation events reported compared to closeness events, and why there were fewer examples of nurses' actions resulting in separation events. Equally well, nurses may accept changed their behaviors during the study period equally they may too be more aware of their deportment and how this impacted on parents' human relationship with their infant. In add-on, this study captured nurse'southward perspectives on closeness and their perspective is likely to exist unlike from that of parents. A study using the same methodology is underway at both study sites to explore parents' perceptions. Having data from the perspectives of both groups will provide an in-depth agreement of parent-infant closeness during NICU hospitalization. A strength of our study is that the findings are based on the perceptions of nurses' from ii different countries practising in units with dissimilar types of design: one single family rooms and the other an open up ward.

Conclusion

From nurses' perspective, both parents and nurses engage in actions to optimize closeness. Nurses considered that parent, infant and NICU-related factors influence closeness. Consequences of closeness and separation events ascend for parents, infants, and nurses. It volition be critical to understand if the strategies employed past nurses are also perceived by parents to promote closeness and minimize separation, as their point of view is essential.

Abbreviations

HAPPY, handy awarding to promote preterm infants happy life; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit

References

-

Moore E, Anderson GC, Bergman Northward. Early on skin-to-pare contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD003519.

-

Conde-Agudelo A, Diaz-Rossello JL. Kangaroo mother care to reduce morbidity and bloodshed in low birthweight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;four:CD002771.

-

Flacking R, Lehtonen L, Thomson G, Axelin A, Ahlqvist Due south, Moran VH, Ewald U, Dykes F. Closeness and separation in neonatal intensive intendance. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101(10):1032–seven.

-

Pennestri MH, Gaudreau H, Bouvette-Turcot AA, Moss E, Lecompte V, Atkinson L, Lydon J, Steiner M, Meaney MJ, Mavan Research T. Zipper disorganization among children in neonatal intensive care unit: preliminary results. Early on Hum Dev. 2015;91(x):601–6.

-

Strathearn L. Exploring the neurobiology of zipper. In: Mayes Fifty, Fonagy P, Target M, editors. Developmental science and psychoanalysis. London: Karnak Books; 2007. p. 117–40.

-

Porges SW, Carter CS. Mechanisms, mediators, and adaptive consequences of caregiving. In: Brown SL, Chocolate-brown M, Penner LA, editors. Moving beyond self-interest: perspectives from evolutionary biology, neuroscience, and the social sciences. Oxford: Oxford University Printing; 2011. p. 53–72.

-

Kim P, Strathearn L, Swain JE. The maternal brain and its plasticity in humans. Horm Behav. 2015. No Pagination Specified.

-

Kim P, Rigo P, Mayes LC, Feldman R, Leckman JF, Swain JE. Neural plasticity in fathers of human infants. Soc Neurosci. 2014;9(5):522–35.

-

Swain JE, Kim P, Spicer J, Ho SS, Dayton CJ, Elmadih A, Abel KM. Budgeted the biology of human parental attachment: brain imaging, oxytocin and coordinated assessments of mothers and fathers. Brain Res. 2014;1580:78–101.

-

Swain JE, Dayton CJ, Kim P, Tolman RM, Volling BL. Progress on the paternal brain: theory, beast models, human brain research, and mental health implications. Infant Ment Health J. 2014;35(5):394–408.

-

Kim P, Leckman JF, Mayes LC, Feldman R, Wang X, Swain JE. The plasticity of man maternal encephalon: longitudinal changes in brain beefcake during the early postpartum period. Behav Neurosci. 2010;124(five):695–700.

-

Lindberg B, Ohrling K. Experiences of having a prematurely born infant from the perspective of mothers in northern Sweden. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2008;67(5):461–71.

-

Nystrom K, Axelsson K. Mothers' feel of being separated from their newborns. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2002;31(three):275–82.

-

Rossman B, Greene MM, Meier PP. The function of peer support in the evolution of maternal identity for "NICU moms". J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2015;44(ane):3–xvi.

-

Fenwick J, Barclay L, Schmied V. Peckish closeness: a grounded theory analysis of women's experiences of mothering in the special care nursery. Women Nascence. 2008;21(2):71–85.

-

Gibbs D, Boshoff K, Stanley G. Condign the parent of a preterm babe: a meta-ethnographic synthesis. Br J Occup Ther. 2015;78(8):475–87.

-

Feeley N, Sherrard K, Waitzer East, Boisvert L. The father at the bedside: patterns of involvement in the NICU. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2013;27(1):72–80.

-

Reynolds LC, Duncan MM, Smith GC, Mathur A, Neil J, Inder T, Pineda RG. Parental presence and holding in the neonatal intensive care unit and associations with early neurobehavior. J Perinatol. 2013;33(8):636–41.

-

Latva R, Lehtonen L, Salmelin RK, Tamminen T. Visiting less than every day: a mark for subsequently behavioral problems in Finnish preterm infants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(12):1153–7.

-

Rand K, Lahav A. Maternal sounds arm-twist lower eye rate in preterm newborns in the first month of life. Early Hum Dev. 2014;xc(10):679–83.

-

Krueger C, Parker Fifty, Chiu SH, Theriaque D. Maternal voice and short-term outcomes in preterm infants. Dev Psychobiol. 2010;52(ii):205–12.

-

Chorna OD, Slaughter JC, Wang L, Stark AR, Maitre NL. A pacifier-activated music thespian with mother'southward voice improves oral feeding in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):462–8.

-

Webb AR, Heller HT, Benson CB, Lahav A. Mother's vocalism and heartbeat sounds arm-twist auditory plasticity in the human encephalon before full gestation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(x):3152–seven.

-

Picciolini O, Porro M, Meazza A, Gianni ML, Rivoli C, Lucco One thousand, Barretta F, Bonzini M, Mosca F. Early exposure to maternal vocalisation: effects on preterm infants development. Early Hum Dev. 2014;90(half dozen):287–92.

-

Nocker-Ribaupierre M, Linderkamp O, Riegel KP. The furnishings of mothers' voice on the long term evolution of premature infants: a prospective randomized study. Music Med. 2015;7(3):20–five.

-

Filippa M, Devouche E, Arioni C, Imberty M, Gratier M. Alive maternal speech and singing have beneficial effects on hospitalized preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102(10):1017–twenty.

-

Caskey M, Stephens B, Tucker R, Vohr B. Importance of parent talk on the development of preterm infant vocalizations. Pediatrics. 2011;128(five):910–half dozen.

-

Caskey M, Stephens B, Tucker R, Vohr B. Adult talk in the NICU with preterm infants and developmental outcomes. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):e578–84.

-

Ludington-Hoe SM, Johnson MW, Morgan Thousand, Lewis T, Gutman J, Wilson PD, Scher MS. Neurophysiologic cess of neonatal sleep organization: Preliminary results of a randomized, controlled trial of skin contact with preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):e909–23.

-

Kaffashi F, Scher MS, Ludington-Hoe SM, Loparo KA. An analysis of the kangaroo care intervention using neonatal EEG complexity: a preliminary study. Clin Neurophysiol. 2013;124(2):238–46.

-

Lyngstad LT, Tandberg BS, Storm H, Ekeberg BL, Moen A. Does skin-to-skin contact reduce stress during diaper modify in preterm infants? Early on Hum Dev. 2014;90(4):169–72.

-

Boundy EO, Dastjerdi R, Spiegelman D, Fawzi WW, Missmer SA, Lieberman E, Kajeepeta Due south, Wall South, Chan GJ. Kangaroo mother care and neonatal outcomes: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):1–16.

-

Athanasopoulou E, Fox JRE. Effects of kangaroo mother care on maternal mood and interaction patterns between parents and their preterm, low birth weight infants: a systematic review. Infant Ment Health J. 2014;35(3):245–62.

-

Cong X, Ludington-Hoe SM, Hussain N, Cusson RM, Walsh S, Vazquez Five, Briere CE, Vittner D. Parental oxytocin responses during skin-to-skin contact in pre-term infants. Early Hum Dev. 2015;91(seven):401–vi.

-

Flacking R, Ewald U, Wallin 50. Positive effect of kangaroo female parent care on long-term breastfeeding in very preterm infants. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2011;twoscore(ii):190–7.

-

Feldman R, Rosenthal Z, Eidelman AI. Maternal-preterm pare-to-skin contact enhances child physiologic organization and cognitive control beyond the first x years of life. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75(1):56–64.

-

Gathwala G, Singh B, Balhara B. KMC facilitates mother baby zipper in low birth weight infants. Indian J Pediatr. 2008;75(1):43–seven.

-

Holditch-Davis D, White-Traut RC, Levy JA, O'Shea TM, Geraldo V, David RJ. Maternally administered interventions for preterm infants in the NICU: effects on maternal psychological distress and female parent-infant relationship. Infant Behav Dev. 2014;37(4):695–710.

-

de Macedo EC, Cruvinel F, Lukasova K, D'Antino ME. The mood variation in mothers of preterm infants in Kangaroo mother care and conventional incubator intendance. J Trop Pediatr. 2007;53(5):344–6.

-

Neu M, Robinson J. Maternal property of preterm infants during the early weeks after nascency and dyad interaction at six months. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2010;39(4):401–14.

-

Feldman R, Weller A, Sirota L, Eidelman AI. Skin-to-Skin contact (Kangaroo care) promotes self-regulation in premature infants: sleep-wake cyclicity, arousal modulation, and sustained exploration. Dev Psychol. 2002;38(2):194–207.

-

Greisen G, Mirante North, Haumont D, Pierrat V, Pallas-Alonso CR, Warren I, Smit BJ, Westrup B, Sizun J, Maraschini A, et al. Parents, siblings and grandparents in the neonatal intensive care unit. A survey of policies in eight European countries. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98(11):1744–50.

-

Franck LS, Spencer C. Parent visiting and participation in infant caregiving activities in a neonatal unit of measurement. Birth. 2003;xxx(ane):31–5.

-

Latva R, Lehtonen 50, Salmelin RK, Tamminen T. Visits by the family to the neonatal intensive care unit. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96(two):215–20.

-

Watson G. Parental liminality: a way of understanding the early experiences of parents who have a very preterm infant. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:1462–71.

-

Lupton D, Fenwick J. 'They've forgotten that I'm the mum': constructing and practising motherhood in special care nurseries. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(8):1011–21.

-

Guillaume Due south, Michelin N, Amrani East, Benier B, Durrmeyer Ten, Lescure S, Bony C, Danan C, Baud O, Jarreau PH, et al. Parents' expectations of staff in the early bonding process with their premature babies in the intensive care setting: a qualitative multicenter study with sixty parents. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:18.

-

Morelius E, Anderson GC. Neonatal nurses' beliefs about nigh continuous parent-baby pare-to-skin contact in neonatal intensive intendance. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(17–18):2620–7.

-

Solhaug Chiliad, Bjork It, Sandtro HP. Staff perception 1 yr later on implementation of the the newborn individualized developmental care and assessment program (NIDCAP). J Pediatr Nurs. 2010;25(two):89–97.

-

Feeley Northward, Waitzer E, Sherrard K, Boisvert L, Zelkowitz P. Fathers' perceptions of the barriers and facilitators to their involvement with their newborn hospitalized in the NICU. J Clin Nurs. 2012;22(3–4):521–30.

-

Russell G, Sawyer A, Rabe H, Abbott J, Gyte G, Duley L, Ayers S, Very Preterm Birth Qualitative Collaborative G. Parents' views on intendance of their very premature babies in neonatal intensive care units: a qualitative written report. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:230.

-

Thomas J, Feeley N, Grier P. The perceived parenting cocky-efficacy of start-time fathers caring for very-low-nativity-weight infants. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2009;32(4):180–99.

-

Vazquez V, Cong X. Parenting the NICU infant: a meta-ethnographic synthesis. Int J Nurs Sci. 2014;one(3):281–xc.

-

Axelin A, Ahlqvist-Bjorkroth S, Kauppila W, Boukydis Z, Lehtonen L. Nurses' perspectives on the close collaboration with parents training programme in the NICU. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2014;39(four):260–viii.

-

Thorne S. Interpretive description. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press Inc; 2008.

-

QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo qualitative information analysis software. 10th ed. 2012.

-

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

-

Kools Due south, McCarthy M, Durham R, Robrecht L. Dimentional analysis: broadening the conception of grounded theory. Qual Wellness Res. 1996;6(3):312–30.

-

Mikkelsen Thou, Frederiksen Chiliad. Family-centred care of children in hospital - a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(five):1152–62.

-

Wigert H, Johansson R, Berg M, Hellstrom AL. Mothers' experiences of having their newborn child in a neonatal intensive care unit. Scand J Caring Sci. 2006;20(1):35–41.

-

De Rouck S, Leys M. Information behaviour of parents of children admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit: Amalgam a conceptual framework. Wellness. 2011;xv(1):54–77.

-

Hoffmann TC, Montori VM, Del Mar C. The connection between testify-based medicine and shared decision making. JAMA. 2014;312(13):1295–6.

-

Close Collaboration with Parents Training Program [http://www.vsshp.fi/en/toimipaikat/tyks/to8/to8b/vvm/Pages/default.aspx#horisontaali1]. Accessed xi Aug 2016.

-

Jiang Southward, Warre R, Qiu X, O'Brien One thousand, Lee SK. Parents equally practitioners in preterm care. Early Hum Dev. 2014;90(11):781–five.

-

Bracht M, O'Leary L, Lee SK, O'Brien K. Implementing family unit-integrated care in the NICU: a parent pedagogy and support program. Adv Neonatal Care. 2013;13(ii):115–26.

-

O'Brien Yard, Bracht Chiliad, Robson Yard, Ye XY, Mirea L, Cruz G, Ng E, Monterrosa L, Soraisham A, Alvaro R, et al. Evaluation of the family unit integrated care model of neonatal intensive care: a cluster randomized controlled trial in Canada and Commonwealth of australia. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15(one):210.

-

Hynan MT, Hall SL. Psychosocial program standards for NICU parents. J Perinatol. 2015;35 Suppl 1:S1–4.

-

Hynan MT, Steinberg Z, Bakery L, Cicco R, Geller PA, Lassen Due south, Milford C, Mounts KO, Patterson C, Saxton Due south, et al. Recommendations for mental health professionals in the NICU. J Perinatol. 2015;35 Suppl 1:S14–xviii.

-

Heinemann AB, Hellstrom-Westas L, Hedberg NK. Factors affecting parents' presence with their extremely preterm infants in a neonatal intensive care room. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102(7):695–702.

-

Wigert H, Hellstrom AL, Berg M. Conditions for parents' participation in the care of their child in neonatal intensive care - a field study. BMC Pediatr. 2008;8:iii.

-

White RD, Smith JA, Shepley MM, Committee to Establish Recommended Standards for Newborn ICUD. Recommended standards for newborn ICU design, 8th edition. J Perinatol. 2013;33(Suppl):S2–S16.

-

Flacking R, Dykes F. Creating a positive place and space in NICUs. Pract Midwife. 2014;17(vii):18–twenty.

-

Rhoads SJ, Light-green A, Mitchell A, Lynch CE. Neuroprotective cadre measure 2: partnering with families - exploratory study on web-photographic camera viewing of hospitalized infants and the effect on parental stress, anxiety, and bonding. Newborn Baby Nurs Rev. 2015;xv:104–10.

Acknowledgements

Nancy Feeley and Anna Axelin are members of the Separation and Closeness Experiences in the Neonatal Environment (SCENE) Research Group. Nosotros wish to thank Kaitlen Gattuso, Tara O'Reilly and Zornitsa Stoyanova for their assistance with recruitment and data collection.

Funding

Nancy Feeley is supported by a Senior Research Scholar Career Award from le Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQS). Christine Genest was supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the Quebec Network on Nursing Intervention Inquiry/ Réseau de recherche en interventions en sciences infirmières du Québec (RRISIQ), and from the McGill Nursing Collaborative for Instruction and Innovation in Patient- and Family-Centered Care. These funding bodies had no office in the design or execution of this study.

Availability of data and materials

Information will not be shared equally these are audio files.

Authors' contributions

Written report pattern: NF & AA. Information collection and analysis: All Manuscript training: NF & AA. All authors have read and canonical the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethical blessing and consent to participate

Ethics Committee of the Infirmary District of Southwest Finland #131/1802/2014.

Research Ethics Commission of the Jewish General Hospital #14-146 Federal wide Assurance Number 0796.

Author data

Affiliations

Respective author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Artistic Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted utilise, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original writer(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zilch/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Feeley, Northward., Genest, C., Niela-Vilén, H. et al. Parents and nurses balancing parent-infant closeness and separation: a qualitative study of NICU nurses' perceptions. BMC Pediatr xvi, 134 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-016-0663-1

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-016-0663-1

Keywords

- NICU

- Parents

- Closeness

- Separation

- Visitation

- Nurses

- Qualitative

Source: https://bmcpediatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12887-016-0663-1

0 Response to "what should the nurse discuss with new parents to help them prepare for infant care?"

Post a Comment